Of all the grains used in the production of different types of whisky, barley makes the most significant contribution to the aromatic palette. For over three hundred years, distillers have paid special attention to selecting the right barley, which represents the most significant expense for a distillery. A true source of life, it is the very starting point of the process of making uisge beatha.

The different varieties of barley for whisky production

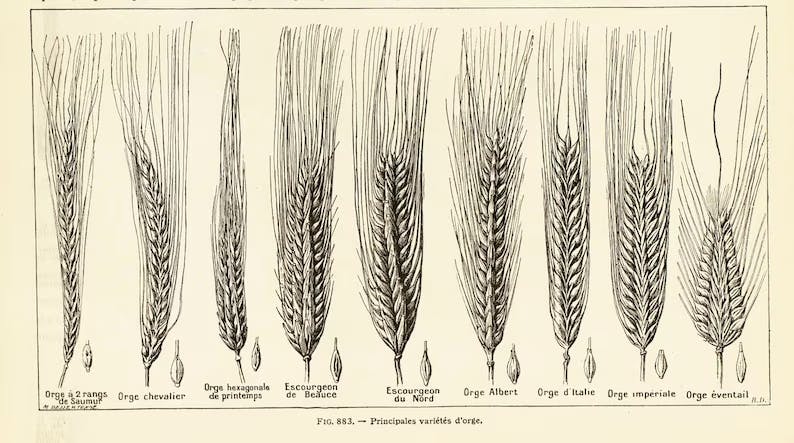

As early as 1678, a certain Sir Robert Moray wrote in one of his articles that malt can only be produced from one cereal, barley. At that time, several varieties were already known. The most renowned consisted of an ear with two rows of grains, while the other, more commonly used variety, had six rows of grains.

This latter variety, known as bere (the ancestor of modern barley), is still cultivated in the Orkney Islands for the production of bere bannock, flatbreads that were long a staple food of the island's inhabitants. Distillers have always favored local barley producers.

However, from the late 19th century, distilleries began to import barley. Driven by the growing popularity of whisky, they received entire shipments of barley, notably from France, Denmark, Russia, and the Baltic States.

One of the main witnesses to this barley rush was the port of Campbeltown on the Kintyre Peninsula, which, in 1873, welcomed shipments of barley several times a week for the thirty distilleries that were operating at the time.

In the 1950s, barley varieties continued to evolve, with new qualities regularly replacing the older ones: Spratt, Plumage, Archer, Proctor, and Marris Otter.

Most of these were native to the north of England, southern Scotland, or Canada. By the end of the 1960s, technological advancements in the harvesting and storage of barley allowed for the appearance of a new Scottish-origin variety called Golden Promise.

Despite being somewhat fragile against mildew (mold), Golden Promise would dominate for nearly twenty years among distillers, representing up to 95% of the barley grown in Scotland. Its decline began in 1985.

Despite the availability of new varieties, some distilleries remained fiercely loyal to Golden Promise, especially Macallan. However, most distilleries shifted to other varieties, such as Optic, which are more resistant and yield higher alcohol content.

Barley selection

Given the multitude of available varieties, a selection is essential. Not all qualities are suitable for alcohol production.

Thus, barley rich in proteins will be used, among other things, for livestock feed or for the production of grain whisky. For the production of malt whisky or Scottish ales (malt-based Scottish beers), distillers and brewers turn to barley rich in starch, which allows for the production of fermentable sugars and, consequently, alcohol.

It is at the time of delivery that distillers check the quality of the barley. They particularly ensure that the grain shows no signs of mold, which, combined with careless harvesting, soaking, and germination techniques, can lead to undesirable flavors.

Malting: between tradition and modernity

Since the 1970s, malting, the first step in the process of transforming grain into alcohol, is mostly carried out outside of distilleries. Today, only six distilleries continue to malt part of their barley on-site: Springbank (Campbeltown), Bowmore (Islay), Laphroaig (Islay), Kilchoman (Islay), Highland Park (Orkney), and Balvenie (Speyside), each thus retaining partial control over this key step in the production process.

Long and costly, this operation is now outsourced to mechanized malteries. Industrial malting offers many advantages over traditional malting.

In addition to time and cost considerations, malteries produce malted barley of consistent quality, taking into account the specific needs of each distillery. Although often seen as a single operation, malting actually consists of three steps:

Soaking

Once harvested, barley enters a natural dormant phase. Composed of a husk that contains an embryo (the future plant) and a starch pocket (energy reserve), barley undergoes several phases of humidification and oxygenation to activate the dormant embryo.

This operation, which lasts between forty-eight and seventy-two hours depending on atmospheric conditions, ends when the moisture content of the grain rises from 15% to over 40%. Germination can then begin.

Germination

The wet barley is spread over malting floors in thick layers of about 30 to 50 cm. The development of the embryo causes the breakdown of the solid walls that protect the starch.

The starch turns into a soft, whitish flour-like substance, and the sugars will be extracted during mashing. The heat generated by the growth of the embryo requires regular turning of the barley mass.

Traditionally, this is done using wooden shovels (shiels) or rakes. This physically demanding operation is repeated an average of three times per day to prevent the sprouts from tangling.

When the sprouts reach a length of two to three millimeters, germination is stopped to prevent the embryo from consuming the sugars in the grain. At this stage, the barley is called green malt. It is transferred to the kiln for drying.

Drying

In the past, drying (kilning) was exclusively done using fuels such as peat, coal, or coke. Coke, derived from coal, is obtained by carbonization at high temperatures, producing a carbon-rich material that burns with little smoke.

Today, malteries are equipped not only with kilns for peat fires, but also with burners that blow in hot air. Once dried, the malt is cleaned of impurities, sprouts, and other residues before being delivered to the distilleries.

Malt aromas

Often considered a mere intermediate step towards alcohol production, malting is rarely mentioned for its contribution to the aromatic palette of whisky. However, depending on the fuel used during drying, the aromatic profile of the malt can differ significantly.

Dried with hot air, it takes on soft biscuity, toasted, and roasted notes.

Dried over a peat fire, it develops roasted, smoky, and medicinal notes that are carried over after distillation.

At the end of the malting process, the malt is stored and then ground into a coarse flour, known as grist, using a malt mill. The resulting grind is made up of 70% grist, 20% husk residue, and 10% flour.

These proportions must be strictly followed to avoid hindering the proper course of mashing. The water will then be able to extract previously inaccessible sugars.

TO EXPLORE WHISKIES FURTHER

La Maison du Whisky has three boutiques in Paris:

In each of these boutiques, you'll find a wide selection of whiskies, rums, sakes, and other fine spirits.

Because a whisky can be described in a thousand words, our experts will be delighted to guide you through the must-try whiskies at La Maison du Whisky.

Follow our tasting calendar for upcoming events, or visit the Golden Promise Whisky Bar, which offers an extensive selection of whiskies and other spirits by the glass.

Discover all our other articles on the blog

Written by

- Quentin JEZEQUEL - SEO project manager at LMDW.

Verified by

- Didier GHORBANZADEH - Wine & Spirits Expert at LMDW

- Clotilde NOUAILHAT - Editorial and Corporate Communications Manager at LMDW