STILLS AND DISTILLATION

Distilleries may swear by the quality of their water, but nothing in the world would make them change the size or shape of their precious stills. This is because a whisky’s character and defining characteristics are forged by the still itself and the art of distillation.

STILLS IN ALL SHAPES AND SIZES

Scottish single malts are distilled using a pot still. This is a kind of kettle with a head and must be cleaned after each use. Its shape varies between distilleries. The onion shape and the boil ball with its spherical chamber are the most wide-spread. Other kinds of still include the classic pot still or lantern still reminiscent of old backroom stills, the pear shape, the bell shape and the extremely rare Lomond still, still used by Scapa and Dalmore, topped with a cylindrical component similar to a patent still, and the column still (a continuous distillation process used for making grain whiskies)..

Whatever their shape, copper pot stills end in a lyne arm connected to a condenser. Copper is used for making stills with good reason. This malleable material acts as a catalyst and eliminates unwanted sulphurous substances. Traditionally coal-heated, direct-fired stills are equipped with rotating arms and a copper chain to prevent the malt beer (wash) from sticking to the bottom of the still or burning. This device is known as a rummager and is not used in steam-heated stills. The latter employ an indirect heating method (inside the still), and are the most commonly used today.

DOUBLE DISTILLATION

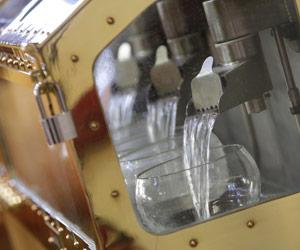

In Scotland, single malt distillation is generally a two-step process. The beer, or wash, produced via fermentation, is first transferred to one or several large stills known as wash stills. They are equipped with small port holes that allow bubbling within the still to be monitored. The low wines obtained once the alcohol vapours have been condensed have a strength of around 25% ABV. They run through the spirit safe which allows the stillman to precisely measure its density. The first distillation is finished once the liquid at the bottom of the wash still reaches no more than 1% ABV. Known as the pot ale, this residue can account for over two-thirds of the initial wash and is used as cattle feed. The low wines are then moved to a smaller still, the spirit still, to undergo a second distillation. The first resulting distillate is moved to the spirit safe to be analysed. Packed full of aromatic esters, aldehydes and acids, the distillation heads (foreshots) contain between 72% and 80% ABV and cloud with the addition of distilled water. These impure foreshots are distilled once more with the next batch of low wine. As the distillation process progresses, the level of alcohol content is reduced. Once the liquid is no longer cloudy, the soon-to-be whisky, the middle cut, remains with an average of between 68% and 72% ABV. The distillation tails (feints) with a strength of under 70% ABV, are rich in sulphur and heavy, powerful aromatic compounds. They are redistilled with the next batch of low wine. Distillation is complete once the liquid still contained within the spirit still is less than 1% ABV. This residue is known as the spent lees, and is processed before being discarded.

STILL AND DISTILLATION IMPACT ON NEW-MAKE SPIRITS

The number of distillations, the size and shape of the stills, the speed at which distillation is carried out, the heating process as well as the angle of the lyne arm all contribute to a whisky’s final character. In Scotland, most distilleries carry out a double distillation process, yet many in the Lowlands have embraced the Irish tradition of triple distillation. Triple-distilled single malts are lighter, boasting elegant floral and fruity notes. The Springbank distillery in Campbeltown is a special case: it distills two and a half times, a complex process that very few specialists can easily explain, but which plays a crucial role in the character of this single malt.

The size of the still used also influences the character of the single malt. The still is heated until the alcohol reaches boiling point, which is lower than the temperature required to boil water. The lightest, very volatile alcohol vapours rise and are transported via the lyne arm. The heavier vapours sometimes fall back into the bottom of the still to be redistilled. This means that the higher the still, the lighter the whisky, as seen at Glenmorangie, home to Scotland’s tallest stills (5.13 m). Conversely, a small still will encourage the production of a fuller-bodied, oilier single malt, such as the Macallan.

The various different shapes of pot still also play an important role. For example, the spherical chamber located between the base and the head of the boil ball allows the heavier alcohol vapours to fall back down to be redistilled, thus producing a lighter whisky. A still heated to a very high temperature will accelerate distillation time, but prove detrimental to quality. A slow distillation process builds the complexity of the future single malt.

The angle of the lyne arm is just as important as the size of the still. A lyne arm with very little incline allows lighter vapour to travel up to the condensor. There are two types of condensor: the traditional worms and the more modern U-shaped tube condensers. Some distillers have recently opted to return to worm condensors, proof that even at this late stage in the process, a whisky’s character remains malleable.

Once the alcohol enters the spirit safe, the stillman reaches peak activity, determining the interval during which he will collect the middle cut. The taste and characteristics of the future whisky (new make spirit) are largely determined by this interval. The more distillation heads contained in the new make spirit, the higher its alcohol content and the richer it will be in aromatic esters. These whiskies are generally light, characterised by pronounced floral and fruity notes. Conversely, a new make spirit rich in distillation tails will feature a lower alcohol content but will be richer, with greater aromatic complexity. A cut carried out too late, however, can result in major and irreversible aromatic defects (sulphurous or vegetable notes). It all depends on specific dosing and great precision.

A pot still can be used for twenty to thirty years. Considering how important each and every individual component is, some distilleries that fear changes in the taste of their whisky, go so far as to reproduce their old stills’ imperfections (such as dents and bumps) in the specifications for their new ones.